By Gibbon

This post was written on June 26, 2020

History is in decline. In terms of a field of interest for study at university, in terms of how it is being taught and in terms of how it is being applied in public. Taken in respective order, each impacts the next and forms a vicious cycle. The result over recent years is starting to show signs of a field that had been diluted of nuance or ignored altogether.

Since 2008 students in the US have increasingly shied away from studying history. Since the financial crisis, in the US, the number of students majoring in history has declined by 30%. In terms of share of bachelor degrees, history is the lowest its been since 1950. As of 2017 no other humanities discipline has experienced as significant a decline as history. The following chart shows the decline isn’t just due to the problems after the financial crisis.

The article the above chart comes from states that students are still studying history but taking it as an elective or option, not a major. Thus they are interested in the subject but because it doesn’t bode well for job prospects (for the most part), and increasingly so post-2008, history isn’t something they wish to stake their future on.

In 2004 it wasn’t uncommon for heads of major corporate institutions or investment banks, such as the one I worked for, to be led by those that had degrees in the liberal arts, including history. However, they were employing only students that studied business. Anyone with a history degree was faced with low paying options once they completed university – teaching, working in a museum – or they had to go back to school and specialise in something that would ensure higher pay. The only solution available to them within history itself, academia, was being closed off as there are only so many tenure positions available in universities across English-speaking geographies. The exception of limited career options applies towards history students at a Yale or Oxford, but this is a rare anomaly.

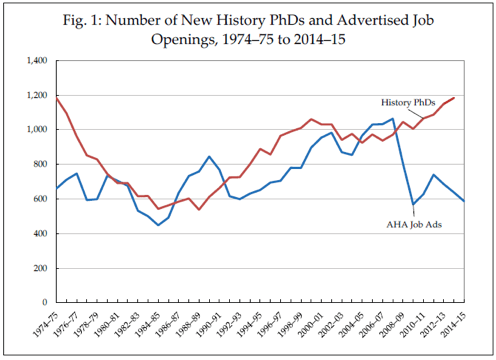

Almost coinciding with the financial crisis is a massive gap between history PhDs and jobs in academic history. The American Historical Association (AHA) estimated in 2013 that only 24% of those with an advanced degree in history over the previous 3 to 15 years were in career positions in academia (beyond professoriate). What may be increasing are part-time or contract positions in History, in which some of the costs may be shared with other departments. Admittedly, there aren’t many records to evidence this correctly, as the AHA points out in its study.

Additionally, those currently in tenure positions are unlike to retire in the near future. The study from the AHA to concludes:

The current age profile of historians in academia represents a significant challenge for doctoral students focused on academic employment and the departments preparing them, as it suggests that the ebb in open tenure-track positions is likely to linger over the next decade. Barring a significant increase in student enrollments to create pressure for new faculty, the demographics of departments today indicate that there will be relatively few full-time positions opening up to replace retiring faculty.

Yet the decline in the numbers of future historians is not all down to external economics and internal opportunities in the academic field. Of those in academia, their methods are appearing ideologically narrow and intransigent, making the subject less interesting. Writing an essay about Barbara Tuchman, I focused on the trend of professional (or academic) historians to pigeon-hole students into a style of writing and focus meant exclusively for academia. The approach will not help prospective historians write history of interest to the general population that could inspire younger readers to study the field. Worse still, it forces pupils to study subjects not in their interest and separates them from the reasons they may have elected history in the first place. These habits tend to turn off potential students or bore existing students, giving them further reasons to avoid history for study or career.

In my essay the point was that Tuchman, armed only with a bachelor’s in history (and literature), produced one of the greatest works about the First World War (Guns of August). She was, and is, repeatedly criticised for her approach by academic historians, despite the enormous popularity of her books. Her work on Guns helped to influence two great modern day writers about history – Margaret MacMillan and Max Hastings – and perhaps a lot more could have been possible. She argued that not pursuing further academic work helped her, in that her writing style benefited by not being poisoned by the techniques being taught by historians in the halls of academia at the time.

My essay included a quote by a journalist that remarked the professionals were “reducing history for a coherent story to an anthropological mishmash of how people baked bread or danced in some forgotten age”. His quote was to criticise the academics that are encouraging students to adopt technical methods focusing on topics that are greenfield or understudied and that the result doesn’t interest many people and does not provide for good prose. So if the youth aren’t going to find a career in academia, they will be armed with writing techniques or knowledge about our past that won’t benefit them independently. My professor remarked how this quote is interesting because it was supporting Tuchman for not studying social history. The journalist in question wasn’t coming from a viewpoint of whether writing about social history is good or bad. The journalist supporter was discussing something more general – how to make history worth reading and studying. In their bubbles, the professionals relegate everything down to technique and theory. Missing the forest through the trees. It isn’t about what subordinate of history something fits into, it is about what should students of history be focusing on that is in their best interest.

Why is someone studying history? Is it to someday write books? Surely, they can’t all be professors? If they are interested in bread baking techniques, fine. But I surmise in the majority of cases this is unlikely their principal interest when they signed up. I witness the encouragement of students to focus on new, but very narrow and dry, subjects with very technical and theoretical approaches for their dissertations. Students have presented some of their ideas in our classes and I hope to god some of them are interested in what they have selected. Most of the topics presented are indeed dull and over-theoretical to the point it could be deemed irrelevant in the eyes of most people. Tuchman warns as much in her book Practicing History. She relays her dismay when a student explains they do not care for their thesis subject. I can not recall the exact subject but that highlights the point – it was extremely dull. How can anyone become a good historian or lean how to write history if they don’t enjoy the subject they are writing about? Why are we forcing these kids to write about things most people don’t care about? Who would want to continue pursuing history in any respect if they come out of their education with that sort of experience? As an article from two clued-in historians explains:

Yet as the historical discipline (like much of the American academy) became more professionalized, especially after World War II, it also became more specialized and inward-looking. Historical scholarship focused on increasingly arcane subjects; a fascination with innovative methodologies overtook an emphasis on clear, intelligible prose. Academic historians began writing largely for themselves. “Popularizer” — someone who writes for the wider world — became a term of derision within the profession.

Another criticism launched regarding my essay was that I did not address the issue of gender. Tuchman didn’t have much to say about the subject and there was no evidence this explains criticism of her work. I am sure it had some role but history must be based on the evidence and facts. I remarked how her female supporters noted disapproval was not about sex, but about the fact she was not in academia. Tuchman never pursued higher education in the subject so it’s not as if she was excluded for any kind of bias. There is a tendency for everything we write about to address such themes as gender. These are very subjective ideas and sometimes in absence of facts, which can be difficult to make evident for such themes. It is not to say that the subject of gender is not relevant, but to let it dominate everything we touch presents the danger of overshadowing other aspects that still remain important. In this case, the issue of gender would help to excuse excessive criticism towards Tuchman by academic historians as being mean to a woman, rather than accuse them of insulated beliefs, and disapproval of techniques that tend to generate more interest in the field outside of academic circles. Again, the previously referenced article continues:

The second issue, closely related to the first, is the hostility toward certain kinds of historical inquiry. Decades ago, the subfields of political history, diplomatic history, and military history dominated the discipline. That focus had its costs: Issues of race, gender, and class were often deemphasized, and the perspectives of the powerless were frequently ignored in favor of the perspectives of the powerful. During the 1960s and after, the discipline was therefore swept by new approaches that emphasized cultural, social, and gender history, and that paid greater attention to the experiences of underrepresented and oppressed groups. This was initially a very healthy impulse, meant to broaden the field. Yet what was initially a very healthy impulse to broaden the field ultimately became decidedly unhealthy, because it went so far as to push the more traditional subfields to the margins.

Lower interest from students, narrow teaching methods and subsequent application of dreary material (or fewer material altogether) in the public realm. Each of these serves to reinforce a repetitive pattern of decline, hastened with each cycle. Students aren’t studying history for external and internal reasons. The ones that do can become disillusioned by the methods they are being taught. There is increasingly less room for professional career paths for them and those are dominated by more insular thinking about narrow topics with limited relevance to the outside world. Those successful in becoming professionals are more commonly put in their position for discovering ‘groundbreaking’ topics but they do not inspire younger people in the subject. With few job prospects or avenues other than a small crack in the door for those with a PhD, the young turn elsewhere. Others lose interest altogether and pursue other things. With each turn the size of the historian pool gets smaller, and its significance in the eyes of the public too.

There aren’t enough diverse viewpoints out there just writing good history about relevant topics. It’s the professorship and not much else. Students need to know there are options for them in history. They need to be engaged by history and allowed to learn how to research and write about what interests them. Subjects and methods being taught should be broad and not emphasized on particular themes or approaches. This is not to say that social history and its equals are not important to consider, but we are impacted by international relations, war, politics and, most of all, economic and financial decisions in so many ways and we seem to have either forgotten that or subordinated its importance in the history departments. These subjects also interest a lot of people, as shown in the continued popularity for finance, economics and international relations at institutions.

With a declining interest in history as a subject and an insulated community of professional gatekeepers, history becomes absent of nuance, ignorant or completely irrelevant in the public sphere. The world is shaped by history in complicated ways. Yet everything is being seen today in black and white. Much of what makes American and British history is starting to become written off as either bad or good. There is no context. If we do not understand history fully in an age of fake news and ahistorical leaders then we are doomed towards disastrous policy, international conflicts and poor leadership. There will be few historians in the future and our understanding of history and its application to topics that impact us will become weaker. We will be left with a few academics that can discuss how the making of bread changed a community in France during the 1800s.